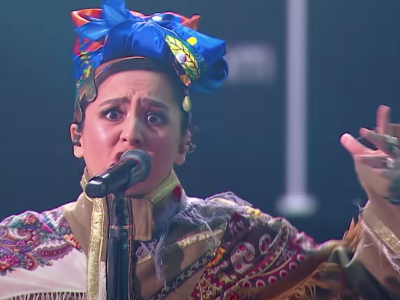

A screenshot from the livestream of the Eurovision first semifinal show.

Since 1956, Eurovision, one of the world’s first truly international song competitions, has been dazzling the world with its over-the-top performances and larger-than-life stars. While it’s garnered a bit of a reputation as being “kitschy” or cheesy due to its incredibly dramatic and often “out there” performances (who can forget the baking grannies or “Hard Rock Hallelujah”), this event is more than just a song competition. In fact, Eurovision has gotten political numerous times over the years.

It has been instrumental in the queer rights movement in Europe and has normalized gender and sexual diversity on the world stage.

This annual contest has also become a way for countries to flaunt their soft power and gain legitimacy — particularly countries newer to the EU that have struggled to make a name for themselves on the European political landscape. Similarly, countries considering EU accession, such as Moldova and countries from the South Caucasus — Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia — are all presenting songs in the 2023 edition, and all have added incentive to cast their country in a good light via the contest.

Last year’s competition, in particular, had some political undertones, as Russia’s war against Ukraine cast a pall on the performances. Because of the invasion and the sanctions that have followed, Russia has been banned from participating in the competition for the last two years. Last year’s competition ended in a bittersweet victory, as the Ukrainian contestants won with their Ukrainian language rendition of “Stefania“ — an homage to motherhood, Ukraine, and nostalgia for better times.

Similarly, Belarus was suspended for three years after it submitted a patriotic and political song in 2021.

While the winners typically host the following year’s competition, Ukraine is unable to this year due to continued attacks from Russian forces. Therefore this year’s event will be held in Liverpool in the UK. Ukraine has been a major Eurovision player since it joined in 2003: it has won three times and was a runner-up twice.

This year’s edition will showcase 37 countries — not all part of Europe, as it includes Australia and Israel. The semi-finals and the final are available on the Eurovision YouTube channel here.

To celebrate this year’s Eurovision competition, Global Voices has compiled this special coverage with pieces discussing everything from language diversity in the competition to the political ramifications of the event.

See our full selection of stories, including archive stories from previous years, below.

Stories about Eurovision 2023: Music is always political

WATCH/LISTEN: What Eurovision tells us about Europe

Missed the live stream of the May 20 Global Voices Insights webinar on the Eurovision Song Contest? Here's a replay.

Russians Aren't Happy About Losing Eurovision, But They Weren't Happy Before, Either

Russia's narrow defeat this weekend in the 2016 Eurovision music contest wasn't the only tension in a competition full of lights, pyrotechnics, and nationalism.

Ukraine's Eurovision 2016 Entry Is About Stalin’s Repressions. Russia Isn't Thrilled.

Ukraine’s entry for the Eurovision 2016 music contest is a song about the deportation of the Crimean Tatars by the Stalin regime. So why are Russian officials upset?

Finland's Eurovision Finalists Sing About Discrimination Against the Intellectually Disabled — From Experience

All of the members of Finnish punk rock band Pertti Kurikan Nimipäivät have intellectual disabilities. They recently won the competition to represent Finland in the Eurovision semifinals.

Russians Hate Eurovision's Bearded-Lady Champion

On the Internet, Russians have reacted to Wurst’s victory with a mix of humor and homophobia.