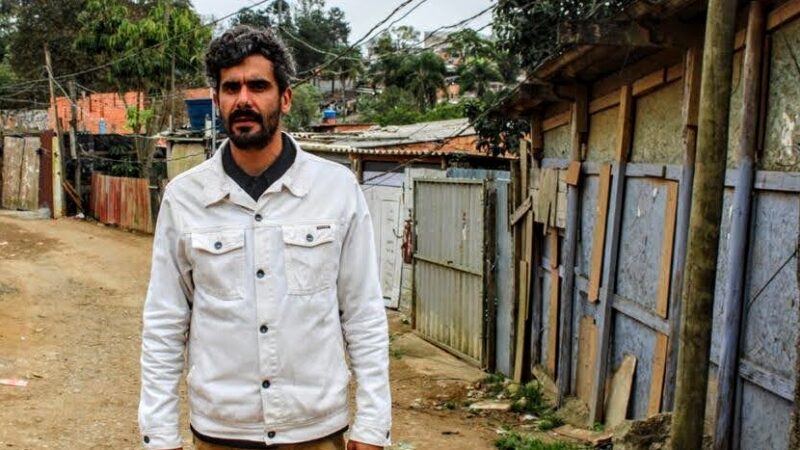

Among the main issues addressed by residents are flooding, lack of forest coverage, and inadequate housing. Photo by Isabela Alves/Agência Mural, used with permission.

This story, written by Isabela Alves, was originally published on October 31, 2025, on Agência Mural’s website. The edited article is republished here under a partnership agreement with Global Voices.

Not expanding landfills in poorer neighbourhoods, promoting environmental education in schools and other spaces, creating a green currency for recycling, and holding big polluters and public authorities accountable for preservation.

These are some of the proposals developed by activists from the peripheries — marginalized, poorer neighborhoods — of São Paulo, Brazil, the largest city in Latin America. They are to be taken to COP 30 (the 2025 United Nations Climate Change Conference), being held between November 10 and 21, in the city of Belém, in the northern Brazilian state of Pará.

In total, about 30 proposals appear in the “Letter from the Peripheries on Commitments for the Climate – The Atmosphere is Tense!,” signed by 50 collectives and 1,000 community leaders. As well as the proposed ideas, the document provides an analysis of the situation in these areas in the face of climate change.

“We plan to connect with people from other countries, other regions and marginalized areas of Brazil, so that together we can present a project shaped by society’s peripheries,” said Edson Pardinho, 50, coordinator of the Peripheral [Neighbourhoods’] Front for Rights, which organized the letter.

The Peripheral [Neighbourhoods’] Front for Rights came out of the collaboration of social movements during the COVID-19 pandemic, when they acted to help families by distributing food, hygiene kits, and masks. Following the pandemic, the collectives continued their work together.

In the months before the COP, the front mobilized activists to discuss climate goals in their neighbourhoods and draft their collective proposals.

“[Climatic changes] first affect the outer peripheries, and only then are they felt in the more protected areas. Those who live in peripheral neighbourhoods have been dealing with climate change for a long time,” Pardinho observed.

The letter presents ideas with the objective of guiding public policies and community practices that promote socio-environmental justice. It emphasizes the importance of strengthening public involvement in decisions concerning their territory. The suggestions include actions aimed at waste management, environmental education, decent housing, a solidarity economy, and basic sanitation.

Marginalized voices speaking about the climate

Jaison Lara is an environmental activist working on culture and the education of children and young people. Photo by Isabela Alves/Agência Mural, used with permission.

The letter highlights that the historical expansion of São Paulo’s peripheral areas was driven by the lack of urban planning. “The city’s rapid expansion was not [socioeconomically] neutral: it prioritized major economic interests, such as those of the real estate market, whose exclusionary logic relegated poorer people to dilapidated, risky areas.”

“People have developed their own technologies to make sure they survive, even with the worsening climate situation,” said Pardinho, a resident of the Dom Tomás Balduíno Settlement in Franco da Rocha, São Paulo.

Mateus Munadas, 34, is one of the founders of the Peripheral [Neighbourhoods’] Front for Rights and a resident of Itaquera district. For him, it is important that peripheral activists attend the COP, as the perspectives of those who truly feel the impacts of the climate emergency daily are never taken into account.

“There are common points of vulnerability between these marginalized neighbourhoods, and there are also many people fighting for change in these areas,” he said.

Among their proposed solutions are actions such as cleaning streams, community vegetable gardens and farms, solidarity groups during storms, environmental support networks, and community communications. In the field of education, social educators, culture collectives, and teachers are working tirelessly to raise awareness about SDOs (Sustainable Development Objectives), and warn about the environmental racism experienced in marginalized areas.

There are also other solutions, such as community reforestation, strengthening recycling cooperatives, expanding rainwater collection networks, and plans for local adaptation guided by the communities themselves, according to sources Mural spoke to.

A place for discussion

Children and teenagers from Jardim Lucélia and Jardim Shangri-lá, from Grajaú, spoke about climate change. Photo by Isabela Alves/Agência Mural, used with permission.

The Guaraní people from the Tekoá Pyau Indigenous Village, in Jaraguá, called for the protection of Indigenous peoples, and highlighted that their survival is essential for environmental preservation.

“It is not only about the increase in temperature, but [also] the survival of human beings who cohabit wooded and forested spaces. They are directly targeted by landowners and real estate speculation,” Pardinho said.

The coordinator of Casa Ecoativa, Jaison Lara, explained that the manifesto also questions the logic behind an event historically composed mostly by older, white, and cisgender men who nevertheless speak on behalf of the diverse range of residents and territories.

“If there are only diplomatic figures [present], the [same] powerful people as always, it will likely be an empty event as it won’t take into account knowledge from the peripheries, quilombolas [settlements of residents descended from enslaved people who escaped to freedom], Indigenous and riverside dwellers,” said Lara.

In one of the meetings, Lara talked to more than 200 children. “These are the main people facing the environmental disasters that have been happening. We are leaving [them] a collapsing planet, and this isn’t their fault. There are no public policies that relate to this age group, that look at these children,” he said.

The housing issue

A key question for those living in the peripheries is the right to housing, especially in areas such as the very south of São Paulo. Here, there are houses built irregularly in the “APAs” (Environmental Protection Areas). In recent months, Greater São Paulo has seen a series of actions by authorities and judicial decisions against these occupations.

“Housing and the environment must go together,” argued Clair Helena Santos, 67, coordinator of the housing movement for Missionária-Cidade Ademar and Cecasul (Citizenship and Social Action Centre – South).

Santos joined the social movement at the age of 17 and has been selected as an activist to attend COP30. “Having housing, I understood that it is the channel for all other human rights: health, education, transport, leisure, and so many others,” she said.

Clair Helena Santos has been an activist for housing rights since the age of 17; she was selected to go to COP30. Photo by Isabela Alves/Agência Mural, used with permission.

The letter to the COP proposes an “end to evictions and violent practices against settlements and favelas,” and programs aimed at people living in at-risk areas, so that they do not find themselves with nowhere to go if anything happens to their homes.

The letter shows the main demands of communities in areas such as Cidade Ademar and Pedreira, regions hit hard by climate change, as they are near dams or sewage flows.

A recent example of environmental impact was the construction of a bridge on Alvarenga Road, which passes over the Billings Dam, one of the largest water reservoirs in São Paulo, affecting aquatic fauna and plants.

“There’s no point in the big guys staying there discussing the environment and fighting floods if the peripheries and social movements are not represented, right? For us, it’s the maxim of nothing about us, without us,” Santos observed.