Screenshot from Eyoha Media’s YouTube channel, showing two hooded guests facing away from the camera during a segment on disputed online donations. Fair use.

A viral act of “kindness”

A TikTok clip began circulating, filmed inside a parked car near Bole, Addis Ababa. The camera faced inward. A man called Tamru sat in the passenger seat, shoulders hunched, voice low, describing illness and daily struggle. The man behind the camera never showed his face. When Tamru finished, a hand entered the frame and pressed a folded wad of cash into his palm.

The clip first appeared on @melektegnaw_ (about 1.7 million followers), a popular TikTok handle that seemingly encourages charity. There are countless others built on the same formula: emotion as the hook, the subject as the thumbnail, a small cash handoff as “proof,” and clicks that translate into engagement and revenue.

On the recording, Tamru asked if there might be longer-term help that could put him back on his feet. The two exchanged phone numbers and a bank account. The man told him to keep praying — that the money came through prayer, and that he was merely a messenger connecting givers and the needy.

The scene hinted at transformation.

The money moved, but the promise did not

After the TikTok clip went viral, people mobilized — and so did the money. Within weeks, more than USD 1,576 (about ETB 260,000) moved through a bank account in Tamru’s name, while an estimated USD 2,120 to 2,4251 (about ETB 350,000 to 400,000) went to accounts he says were tied to associates of the masked organizer. Much of it came from members of the Ethiopian diaspora who believed they were lifting a stranger out of poverty. The funds were meant to buy Tamru a Bajaj, a three-wheeled taxi that could have put him back to work.

Instead, Tamru recalls being told over the phone by the same man who met him in person — the faceless figure in the earlier clip who filmed him handing over the wad of cash shown on TikTok to send more money for ‘tax clearance,’ ‘transport fees,’ ‘processing,’ and even ‘frozen account’ penalties. By the end, he estimates he wired USD 1,212 (about ETB 200,000) from funds deposited into his own account. Only after the promises kept shifting did he take his story public, sitting for a nearly three-hour interview on Eyoha Media, a YouTube channel with a large audience, hoping exposure might force answers.

The men behind the masks

In that interview, Tamru never mentioned @melektegnaw_, even though the clip first appeared there. Instead, he said the man behind the camera was ‘Baladeraw’ — of the TikTok channel @baladeraw — and added that when the host phoned him, he thought he recognized the voice.

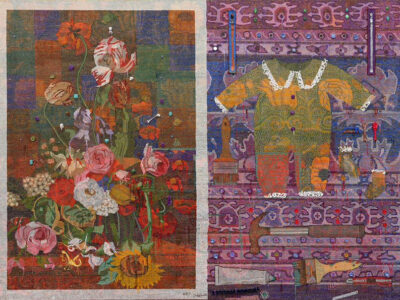

Baladeraw’s “charity” brand mixes faith, emotion — and opacity. Screenshot from Baladeraw’s TikTok page. Fair use.

From my review, both channels use the same staging: hoods up, the camera fixed behind the “giver,” and slogans printed across sweatshirts — “the trustee” (ባለአደራው) and “the messenger” (መልክተኛው). They frame anonymity as religious humility. It remains unclear whether this involves two men, a coordinated group, or one operator using multiple identities.

A screenshot from @melektegnaw_ on TikTok, whose viral “charity” clips turn compassion into clicks amid growing scrutiny over how donations are handled. Fair use.

What is clear is the pattern. Both accounts follow the same template: a humanitarian persona across Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok who appears faceless, selfless, and devout. Each video traces the same emotional arc — a vulnerable subject, an anonymous “rescuer,” and a small on-camera handout — crafted to look like spontaneous charity while evading scrutiny.

Faith, optics, and profit

On Facebook and TikTok, a stream of handheld, emotional clips does most of the legitimizing. Platforms reward the optics; audiences read them as proof. A cursory look at Baladeraw turns up a Facebook page labeled “Charity Organization” and a website — trappings of credibility with little visible oversight.

That credibility converts to cash. Baladeraw reports raising more about USD 10,958.96 (more than ETB 1.5 million) through Chapa, an Ethiopian-licensed payment gateway regulated by the National Bank of Ethiopia as a “payment system operator.”

Meanwhile, both men’s TikTok presences blur personal and fundraising content. TikTok’s own rules state that fundraisers must be verified organizations — with registration, a website, and at least 1,000 followers — and, in some regions, additional tax documents. Yet these creators solicit donations as private users, outside TikTok’s verified fundraising tools, raising basic questions of compliance and transparency that the platform has not addressed.

On Facebook, Baladeraw’s “Charity Organization” page remains active, even though Meta’s policies explicitly ban charity fraud and scams. Why a masked operator with no public accounting can present as a charity remains unclear.

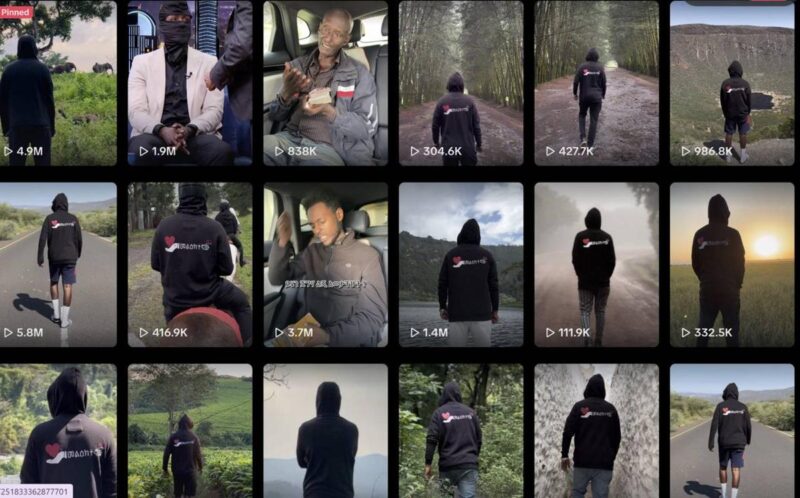

Anatomy of a confession that wasn’t

In a follow-up, Eyoha Media brought in both @melektegnaw_ and “Baladeraw,” hoping to settle the story. But instead of pressing for documents or receipts, the host guided Tamru toward retracting his accusations. Identities were obscured: no on-screen names or identifiers appeared; both fundraisers wore hoods, kept their backs to the camera, and only their voices were audible. No documentation was presented or reviewed. The hooded fundraisers walked away without answering how much was raised, who handled it, or whether any of it reached the beneficiary.

On his website, Baladeraw also embeds a clip from his interview with EBS, one of Ethiopia’s largest private broadcasters — hooded, facing away from the camera, his voice the only part revealed. The hosts never addressed the obvious: anonymity may be defensible when one gives their own money, but not when soliciting the public’s. Ethiopian law requires registered charities to disclose finances, keep records, and file reports. Masked fundraisers with donation links cannot claim exemption. Yet no one asked about this. The spectacle continued: the benefactor unseen, the gaze unflinching, the suffering on display.

The unmasking

In a late twist, the person behind @melektegnaw_ unmasked himself on Seifu on EBS, Ethiopia’s top late-night show, calling his work “God’s work.” He blamed impostors using look-alike accounts, said he posts beneficiaries’ own bank numbers so money goes ‘directly’ to them, and cited a 20,000 ETB (about USD 120) diversion he claims was the fault of an intermediary. He denied taking commissions, describing himself as a messenger who shares ‘verified’ cases and runs small drives like the ‘100 birr (about USD 0.60) challenge.

As in the Eyoha Media and EBS appearances, Seifu let him pass unchallenged, skipping basic questions of accountability and transparency. None of his claims were independently verified, and key issues remained unanswered: who verifies these cases, what records exist, and who is responsible when funds disappear.

The bigger story: Platforms, poverty, and profit

Ethiopia’s social media crisis is often framed around hate speech and misinformation. But scams thrive too — especially in under-served languages. In April 2023, AFP’s Ethiopia fact-check desk exposed a viral in Oromo Facebook post falsely promising “free travel to America” for two million Africans; the US Embassy confirmed it was a scam, and the link led to a job-search app, not visas.

Globally, the same pattern persists. Internal Meta documents reviewed by Reuters revealed that about 10 percent of its 2024 revenue was projected to come from ads tied to scams or banned goods. The company estimated users see 15 billion scam ads a day. In 2023, UK authorities reported that 54 percent of all payment scams involved Meta platforms.

These aren’t isolated incidents. They are symptoms of an attention economy where fraud scales faster than oversight — and where the platforms profiting from engagement have little incentive to act.